16 05 17 — 15:34

a survey.

The answers to a survey of believers from two monotheistic religions will be presented in the glass palace, and juxtaposed in an audio composition. Islam was forcibly introduced in the central highlands of Afghanistan as the religion of the conquerors around 1000 AD (Mahmud of Ghazni, the ‘destroyer of the idols’) and replaced Buddhism and other forms of religion, which had been predominant for over a thousand years prior to this.

The beginning of Sikhism was established in the Punjab (North India) at the beginning of the 16th century from the teachings of Guru Nanak around the same time as the Reformation in Germany. It developed out of a reformist approach and contains certain elements of Hinduism and Buddhism, while aspiring to go beyond them, with the aim of using religious wisdom for people’s everyday lives.

The survey

Several questions were raised in the central highlands of Afghanistan and Sikhs in Amritsar (Punjab, North India):

What do you think in general of the idea of reforming a religion?

What do you think of borders?

The recorded responses in several languages, intentionally left untranslated, are condensed into a polyphonic sound composition, with resonance speakers making the glass walls of the cube sound. The visitor of the cube can gain different audio impressions of the dynamically evolving composition, depending on the location and the activity of the movement.

On the other hand however, visitors to the glass palace, who speak either Dari or Farsi, or Urdu or Punjabi, could also translate the texts – Dari speaking Afghans and Iranians, and people from Pakistan and North India who speak Punjabi. All visitors are invited to leave written or audio comments in the cube. During the course of the project these comments are edited and, where appropriate, integrated into the composition.

As a further option, the spoken responses could be offered in a translated form, either as a transcript or as an audio commentary, e.g. available on the mobile phone of the visitor. The obstacle of the language barrier can thus be overcome by different means.

Objects and image materials

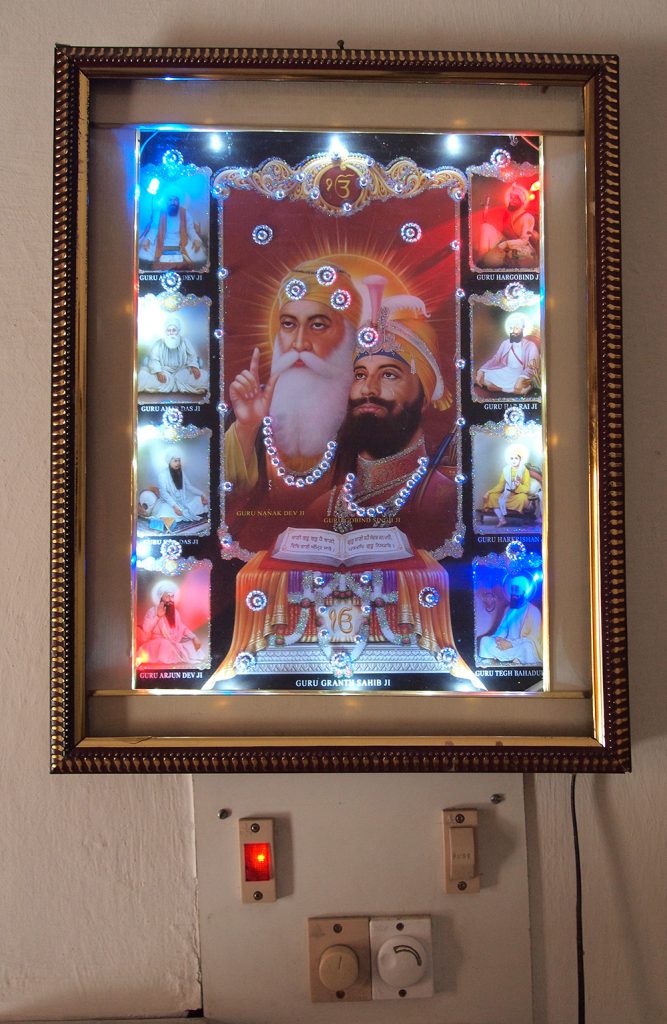

In addition, objects, videos, photographs and texts from the respective areas (Afghanistan, Central Highlands and Punjab, North India) are presented in the glass cube. From the Central Highlands of Afghanistan various items such as flags, nails, threads, sacred pieces of wood and various types of incense are presented or installed in the glass cube. Image materials are partly integrated in the form of transparent films or in conventional prints on paper. Religious display cabinets from Amritsar are presented, as are ritual garments, which are normally worn in the Golden Temple.

Cuisine

Both regions and religious forms combine, among other things, the preparation of ritual dishes, which are consumed in the community, but are also donated to the poor. Visitors will be offered appropriate dishes during the glass palace opening. The collective consumption of food has a sacramental significance in Christian religions. In this way too, the global can be connected with the local.

Central Highlands, Bamiyan Province, Afghanistan

In the area of today‘s Afghanistan, Islam has been the dominant religion in its Shiite version for 1000 years. Shia Islam is, after Sunni Islam, the second-largest branch of Islam and split very early. The cause was not a reformist one, but rather religious power politics and a dispute about the legitimate successor to Muhammad. Buddhism, among several other religious forms, prevailed for more than 1000 years prior to this. This is still evident today, for example in the giant Buddhas of Bamiyan, destroyed by Taliban 16 years ago, and in the huge Buddhist monastery complex of Mes Aynak, which is likely to fall victim to copper mining in the near future. Persian, as well as Roman-Greek and Zoroastrian forms, were able to exist parallel to Buddhism in those times. This is also evident in coin finds from the Kushan period (around 200 AD) with illustrations of Buddha, Helios and Ardoksho, an ancient Persian mother deity. It is noteworthy that today, in some religious customs, elements of Buddhism and pre-Buddhist religion have been preserved. My work over several years in the Central Highlands of Afghanistan enabled me to interview people there.

Amritsar, Punjab, North India

Sikhism originated about 500 years ago in North India after trips of the religious founder Guru Nanak to Mecca, Iraq, Afghanistan and Europe. This movement, which can be regarded as a reformation with its critique of prevailing religious dogmas, aimed to achieve more fraternity among people and to avoid egoism. Guru Nanak was a strict opponent of the caste system and preached in front of Hindu temples with his disciples and also in front of mosques. A well known quotation from Nanak is: “There is no Hindu, there is no Muslim, there are only creatures of God.” He was also a critic of certain religious rituals, which would hinder genuine religiosity. A trip to Amritsar to the Golden Temple of Sikhs and meetings figures at Khalsa College enabled a survey of some Sikhs and the experience of this religious community. The questionnaire must not be confused with a scientific-sociological or ethnographical study, since it does not have standardised questions. Indeed, no scientific findings can be drawn from the survey answers, except for the audio files used in the composition. However, the project will include ethnographical and sociological components. The survey has been and will be continued via modern media networks after my departure.